The following is a chapter from the book ‘Orality Breakouts – Using Heart Language to Transform Hearts‘. A chapter will be posted here each week.

Chapter 11 – Practices in Orality: The Existence, Identification, and Engagement of a People’s Worldview

By James Slack

Christ’s desire and intention is to reach the lost by changing each person’s heart and habits according to His salvation plan and message. Every ethnic people group in the world is included in His purpose and is distinctive in its language and culture. In order to be most effective, evangelizers should initially identify a group’s worldview to present the Gospel through relevant means, and especially through using relevant heart language words.

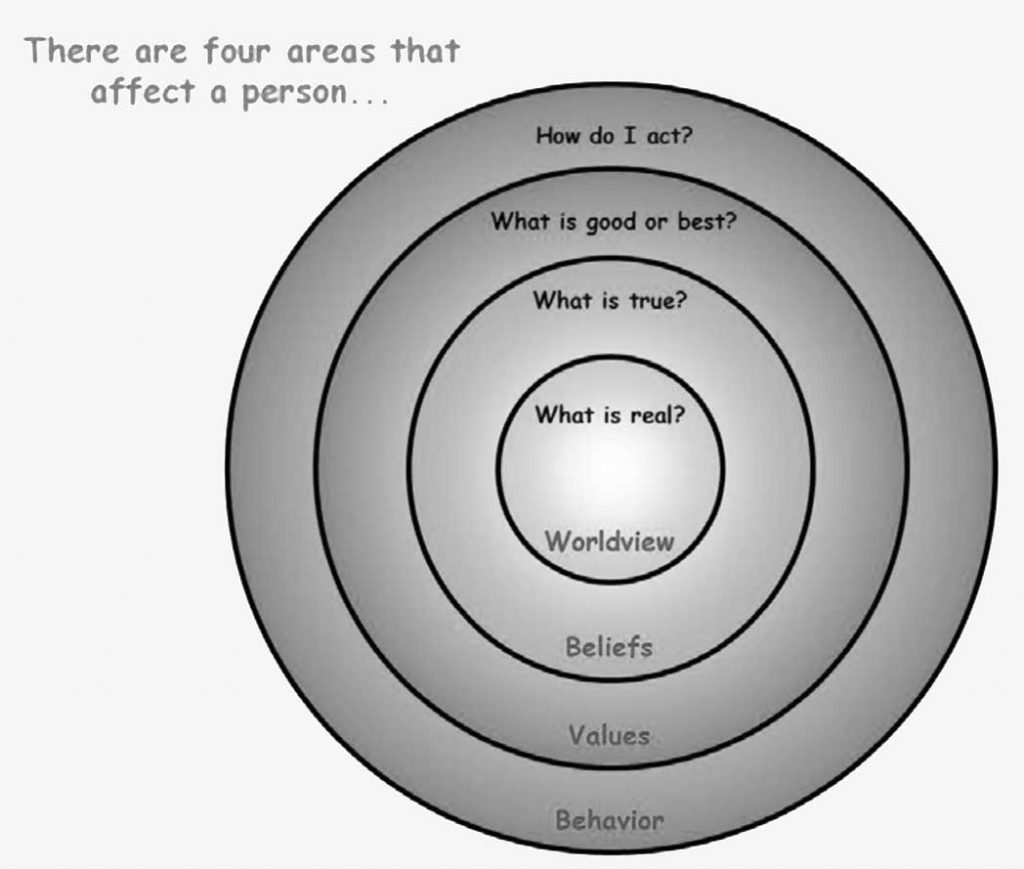

Worldview is simply the way a person views his or her world. It is a composite of the core beliefs, values, cultural views, and practical lifestyle habits that characterize a person within a specific ethnolinguistic people group. Worldview identification is particularly vital when working among persons and ethnic groups with a preference to learn and communicate orally. This chapter is a practical exploration of worldview identification and its application to witness and church planting. Let’s start with the basics.

Where do we get our worldview?

The basis of worldview is found in the Great Commission. Making disciples among the panta ta ethne1 (each and every ethnolinguistic people group) is at the heart of Christ’s Commission. The roots go back to God’s call of Abraham (Gen. 12:1ff) and continue through more than one hundred Old Testament references such as Psalm 2: “Ask of Me and I will give you the nations [goyeme] for your inheritance.” (Hebrew goyeme means “ethnic people groups.”) The question is, how many ethnic people groups do we have in our current church-planting inheritance?

The Great Commission began in Genesis and continues through Revelation 21:22-23, where God reveals His desire to have people from every tribe, tongue, and ethnic group in heaven. Although “making disciples” is the major emphasis of Christ’s Great Commission, the arena for this activity is the panta ta ethne (translated as “all nations” in most English versions, but translated from Hebrew and Greek as “all the ethnic people groups”). God’s expectation is clear: He wants all Christians to engage and evangelize every ethnolinguistic people group, starting in their Jerusalem and continuing to their Judea, Samaria, and uttermost (Luke 24:47; Acts 1:8).

The Great Commission began in Genesis and continues through Revelation 21:22-23, where God reveals His desire to have people from every tribe, tongue, and ethnic group in heaven. Although “making disciples” is the major emphasis of Christ’s Great Commission, the arena for this activity is the panta ta ethne (translated as “all nations” in most English versions, but translated from Hebrew and Greek as “all the ethnic people groups”). God’s expectation is clear: He wants all Christians to engage and evangelize every ethnolinguistic people group, starting in their Jerusalem and continuing to their Judea, Samaria, and uttermost (Luke 24:47; Acts 1:8).

The basis of the Great Commission is also seen in Matthew 28:19-20 (short form of the Great Commission) and Luke 24:44-53 through Acts 1:1-2:47 (long form of the Great Commission). Most Christians recognize the “making disciples” part of the Great Commission, but few have understood that the venue for making disciples is the panta ta ethne. We are to identify and engage every ethnic people group from our Jerusalem to the uttermost (Acts 1:8). Even fewer Christians have understood that Christ expects ethnic people group evangelizers to communicate the Gospel in each ethnic group’s heart language. 2 We know that those who believe are to be baptized and gathered into local churches. Many, however, have failed to pick up on “engaging them in their heart language.”

Our task is to identify the ethnic people groups around us, and evangelize them one by one in their heart language. However, if several ethnic people groups are gathered into one multicultural Bible study, it is very difficult to obey the Scripture by engaging each person in his or her heart language.

Our task is to identify the ethnic people groups around us, and evangelize them one by one in their heart language. However, if several ethnic people groups are gathered into one multicultural Bible study, it is very difficult to obey the Scripture by engaging each person in his or her heart language.

It is important to realize that God has significant reasons for underlining the use of heart language when evangelizing an ethnic people group. Most ethnic cultures in the world are composed of oral learners and communicators who can only understand the details of the Gospel in their heart language. If we want to identify clearly with a people group, we will learn their heart language. The choice of their heart language will let them know we came specifically to address them.

For more than two hundred years Christian missionaries, anthropologists, and others have begun to understand, through research, the importance of identifying an ethnic people’s worldview and evangelizing and discipling them in their heart language. The bottom line of that research is that there is no substitute for working in a people’s heart language. Failure to work in the heart language and failure to identify the worldview of the people group are just two reasons why some ethnic people groups have remained unreached for centuries.

Not only does each person have a unique fingerprint and DNA that is unlike anyone else’s, but each person must approach the Lord individually concerning his or her spiritual condition. What lies beneath these truths is the reality of worldview. Each person has his or her own worldview absorbed from the ethnic culture in which he or she lives.

But because worldview is unconsciously formed over time, individuals are seldom aware they have a worldview. One cannot simply enter their setting and ask them to explain their worldview to someone from the outside. Most have never heard the term “worldview.” A culture also has its own worldview, which is actually a composite of all the persons who have lived in that culture from its beginning. And worldviews are changing generation after generation— although in isolated and insulated cultures the worldviews of the people and the culture are more homogeneous. This is especially true in oral cultures.

How is our worldview formed?

Childhood educators and researchers tell us that 45-60% of a person’s worldview is formed and functioning by the time a child is five or six years old. Beliefs will have formed, along with respect for certain things and people. By age eleven or twelve, 60-80% of a person’s worldview is formed. It is interesting that in the Old Testament and until today, Judaism set twelve years as the “coming of age” for a boy. As his or her worldview is confirmed, the child tends to be reasonably at peace with him or herself and others he or she trusts. If a child’s worldview (whether right or wrong in itself) is increasingly contradicted by people in his or her own worldview grouping, or through outside worldviews, coping becomes a serious issue.

Childhood educators and researchers tell us that 45-60% of a person’s worldview is formed and functioning by the time a child is five or six years old. Beliefs will have formed, along with respect for certain things and people. By age eleven or twelve, 60-80% of a person’s worldview is formed. It is interesting that in the Old Testament and until today, Judaism set twelve years as the “coming of age” for a boy. As his or her worldview is confirmed, the child tends to be reasonably at peace with him or herself and others he or she trusts. If a child’s worldview (whether right or wrong in itself) is increasingly contradicted by people in his or her own worldview grouping, or through outside worldviews, coping becomes a serious issue.

Again, it is imperative for evangelizers to identify and understand the worldview status, situation, and setting. Barre Toelken says,

Every child grows up surrounded by a number of cultural, personal, and physical features that provide its first—and perhaps its most lasting—set of perceptions about the world and its operation. In the earliest years, the child is learning more about its language than it will ever learn again, and at this time of life just as much is learned about cultural context and physical surroundings. No wonder that people in different ethnic, economic, and regional groups have the feeling that they live in different perceptual worlds: indeed they do.3

Researchers such as Jane H. Hill and Bruce Mannheim add:

An individual’s personality is the complex of mental characteristics that makes them unique from other people. It includes all of the patterns of thought and emotions that cause us to do and say things in particular ways. At a basic level, personality is expressed through our temperament or emotional tone. However, personality also colors our values, beliefs, and expectations. There are potential factors that are involved in shaping a personality. These factors are usually seen as coming from heredity and the environment. Research by psychologists over the last several decades has increasingly pointed to hereditary factors being more important, especially for basic personality traits such as emotional tone. However, the acquisition of values, beliefs, and expectations seem to be due more to socialization and unique experiences, especially during childhood.4

N.T. Wright, British preacher and New Testament scholar, provides insight into how stories relate to worldview:

Human life…can be seen as grounded in and constituted by the implicit or explicit stories which humans tell themselves and one another. This runs contrary to the popular belief that a story is there to ‘illustrate’ some point or other which can in principle be stated without recourse to the clumsy vehicle of a narrative….Stories are a basic constituent of human life; they are, in fact, one key element within the total construction of worldview.5

It is clear from these quotes that watching people do what they do in normal living is the best source of worldview information. To speed up the “watching process,” we can ask people for their famous stories, fairy tales, folklore, music, and any literature the people group may have.

So how can you identify the worldview of your people of choice to evangelize? Start by looking at an ethnography that has been identified by a professional anthropologist. A university librarian can help you research actual ethnographies; some of these will help in understanding much of this discussion on worldview. Also, the Caleb Project has a large number of worldview-type studies conducted on cities and peoples around the world. These are based on the Exploring the Land manual.6 Some of their reports can be shared and provide good examples of worldview identification. Note that most of these studies, conducted by lay persons, do not represent extensive and detailed worldview work. Personnel of the International Mission Board, SIL/Wycliffe, and New Tribes Mission regularly conduct worldview studies and can provide copies which can be shared publically.

What do we do with the information on worldview?

Below is a step-by-step guide to developing a strategy to use the worldview information you have acquired:

- Develop a glossary of words in the ethnic language to be used when talking with the people, especially about gospel matters.7

- Determine the culturally appropriate ways of meeting, connecting with, addressing, inviting, and gathering individuals from this ethnic group into a small group for gospel-sharing purposes, either sooner or later.

- Determine how best to organize them into Bible study or Evangelism Track groups, (e.g., women with women, men with men, or women and men in a mixed gathering).

- Analyze the worldview facts of your group to identify the major worldview barriers and worldview bridges you will need to address specifically as you present the Gospel. Pay special attention to how the Gospel will be presented in light of cultural issues.

- Choose the specific Bible stories that will address the particular issues described in #4.

- Develop an introduction to each story to provide the hearers with listening tasks for each story so they can recognize and dialog about the specific worldview issue the story addresses.

- Construct biblical/theological descriptions of those issues that will arise during storytelling dialog and during everyday discussions as a result of the storying and presence of evangelizers.

- Finalize the evangelism, church planting, discipleship, and future leadership training tracks/phases.

Worldview and heart language are key issues in successful evangelism and church planting. The guidance given in this chapter and elsewhere in this book will bring you closer to fulfilling your heart’s desire as you witness the movement of God’s Spirit among your chosen people group.

Notes

1 The Greek phrase panta ta ethne in Matthew 28:20 and elsewhere is usually translated “all nations.”

2 See Acts 2:5-11, where “in their language” is emphasized three times, including the phrase “heart language.”

3 Barre Toelken, Dynamics of Folklore (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1996), 269.

4 Jane H. Hill and Bruce Mannheim, “Language and Worldview,” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1992): 381-406 (accessed 14 July 2010).

5 N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 1992), 38.

6 Exploring the Land: Discovering Ways for Unreached Peoples to Follow Christ (Orlando, FL: Caleb Project, 2003) can be purchased at Amazon.com or through Pioneers International.

7 Check first with SIL/Wycliffe and New Tribes as they may already have a glossary related to your ethnic group’s language.

Biography

James Slack is a recognized researcher in missiological, ethnographic (worldview), urban, and church-planting movements, materials development, and global training roles. As a missionary in the Philippines he served as an urban evangelism consultant, church planter, educator, and urban strategist, and conducted oral and literate research. His accomplishments in Bible translation, and Chronological Bible Storying as a means of communicating the Gospel to oral learners and communicators, are recognized globally. Jim serves with the International Mission Board, SBC, as he follows his passion to reach ethnolinguistic people groups.

« 4.2.20 Foundation & IBLT launch School of B...Gimchua’s Family »