The following is a chapter from the book ‘Oralities and Literacies: Implications for Communication and Education‘. A chapter will be posted here each week.

Chapter 4 – Encountering Text as Multimodal Experience

by Dr. Calvin Chong

Part 1: Multi-textured and Multimodal Learning Experiences

The Emerging Multimodal Communications Landscape

The world outside school today is replete with words married to images, sounds, the body, and experiences…This new world is a multimodal world. Language is one mode; images, actions, sounds, and physical manipulation are other modes. Today, students need to know how to make and get meaning from all these modes alone and integrated together. In the 21st century anyone who cannot handle multimodality is illiterate. (Serafini 2013, xi)

Recent history has seen the emergence of new ways of expressing ideas and representing reality. This evolution toward rich and textured multimodal representation has dramatically altered the way humans communicate with each other and opened the door to a broader range of blended modalities experienced in communication events.

The influences fueling the expanding pervasiveness of multimodality in the twenty-first century include:

- Market responsiveness to the growing experience economy (Berridge 2007; Sundbo and Darmer 2008; Pine and Gilmore 2011; Newbery 2013; Kuiper and Smit 2014; Lorentzen and Hansen 2014; Rose and Johnson 2015)

- Experimentations with new formats in presentations and conferences (Brown 2005; Klein Dytham Architecture Staff 2007; Owen 2008; Gray, Brown, Macanufo 2010; Lupton 2011; Lankow, Ritchie, and Crooks 2012; Shankar 2012; Craig and Yewman 2013; Krum 2013; Baker 2014; The Edcamp Foundation 2014)

- Expanding presence of installation art in corporate events and public spaces (Rosenthal 2003; Oliveira, Oxley, and Petry 2004; Bishop 2005; Du Cros and Jolliffe 2014; Spring 2015)

- Increasing influence of design thinking in everyday life (Brown 2009; Sherwin 2010, Kumar 2012; Boys 2014)

- Rapid advancements in new digital technologies and user interface development (Jewitt 2006; Moran 2010; Tzovaras 2010; Poe 2013; Oviat and Cohen 2015).

Key to the study of multimodality is the concept of the multimodal text. This concept is described and explained by Anstey and Bull (2010) as follows: A text may be defined as multimodal when it combines two or more semiotic systems. There are five semiotic systems in total:

- Linguistic: comprising aspects such as vocabulary, generic structure and the grammar of oral and written language

- Visual: comprising aspects such as color, vectors and viewpoint in still and moving images

- Audio: comprising aspects such as volume, pitch and rhythm of music and sound effects

- Gestural: comprising aspects such as movement, speed and stillness in facial expression and body language

- Spatial: comprising aspects such as proximity, direction, position of layout and organization of objects in space.

In addition to Anstey and Bull’s exploration of multimodality in terms of “linguistic,” “visual,” “audio,” “gestural,” and “spatial” interactions, alternative descriptions of modes have also been proposed. Jewitt’s research on the impact of new technologies on learning for example features “image, colour, speech and sound effect, movement and gesture, and gaze” as discrete yet interrelating semiotic modes (Jewitt 2006, 17). Galbraith and James on the other hand feature “print, aural, interactive, visual, haptic, kinesthetic, and olfactory” in their list of modes (James and Galbraith 1985, 20-21). Tileston includes linguistic (speech and writing), nonlinguistic (mental pictures, olfactory sensations, kinesthetic sensations, auditory sensations, and taste sensation), and affective modalities (feelings and emotions) in her classification (Tileston 2003, 6-7). Finally Rowsell features “film, sound, visual, interface, video games, space, movement, word, and textile” as expressions of multimodal texts within which semiotic resources are embedded (Rowsell 2013).

While the classifications above illustrate differences in what constitute modes of communication, they share in common the recognition that communication acts often involve complex transmodal interactions. These moves toward understanding communication events in multimodal terms and creating multimodal, multisensory consumer/learner experiences are rapidly reshaping the communications landscape. At the same time, they are also driving current research in pedagogy and educational practice (Jewitt 2006; Anstey and Bull 2010; Bean 2010; Bowen and Whithaus 2013; Rowsell 2013; Serafini 2013; Starc, Jones, and Maiorani 2015).

Reframing the academic discourse and transforming praxis in orality studies

It is against this backdrop of an increasingly multimodal world that a quick glance at the developments in orality studies is cast. Amongst the promising directions that orality studies is moving toward is its emphasis on exploring interactions between speech and the written text. In his paper discussing oral discourse in a world of literacy, James Paul Gee points out (twice) how “speech and writing so often go together, and…trade on contextual interactions for interpretation.” (Gee 2006, 154 & 155) Two important points flowing from these realities are worth rehearsing.

First, because the interactions are embedded in specific contextual communication acts, Gee proposes that it is more useful to study communication genres in action rather than individual elements in isolation. He thus writes:

…it is often better to ask about a particular genre of language (e.g., lectures, which though spoken, are writing-like in some ways, or family letters, which though written, are spoken-like in some respects) than writing or speaking per se. This is all the truer today with things like instant messaging and chat rooms, since these are in some ways like face-to-face conversations, but are written. (Gee 2006, 154)

In addition, because communication events are also social events, Gee points out the value of studying speech-writing interactions in the context of social practice:

…it is often better to study social practices that include both writing and speech, as well as various values, ways of thinking, believing, acting, and interacting, and using various objects, tools, and technologies (e.g., practices in courtrooms, secondary science classrooms, graffiti-writing urban street gangs, or urban tagging groups) than it is to look only at writing or speech per se. (Gee 2006, 155)

In line with Gee’s emphasis of exploring interactions across semiotic systems, Charlotte Eubanks offers a useful critique of the older model of exploring orality which emphasized “separate ontologies, exclusive methodologies, and different disciplines” for orality and literacy (Eubanks 2014). Instead, she envisions the new orality as one that features spoken elements interlocked with other elements such as literature, sound, music, gestures, and performances.

Similarly, Lourens de Vries draws attention to the present move to explore closer interconnectedness between the spoken and written text in bible translation (de Vries 2015). Critical to de Vries’ exploration is the prominence he places on local linguistic, historical, and cultural conditions that shape the nature of interfaces between speech and the written text.

Like the developments in multimodality studies, Gee, Eubanks, and de Vries represent the current school of thought which is now framing the academic discourse and transforming praxis in multiple fields including anthropology, sociology, linguistics, literature, performance studies, bible translation, language teaching in schools, literacy education, and teaching training. This move towards viewing communication acts and learning experiences as feature-rich and multi-textured offers fresh possibilities in research and teaching practices for both the church and theological institutions.

The push toward multi-textured approaches in the educational ministries of the church

As with the shifts in thinking and recalibration of mental models within multimodality and orality studies, there too is evidence that educational ministries of the church are advocating diversity of educational experiences and integration of learning modalities. In their book Contemporary Approaches to Christian Education, Jack Seymour and Donald Miller (1982) invite Christian educators from different traditions to write on five different approaches to Christian education.

The critical task of articulating different approaches to Christian education is appropriate since there is a tendency amongst Christian educators tutored in particular approaches to present what they are acquainted with as the only legitimate, scripturally validated expression of Christian education. In the book therefore, Seymour and Miller draw attention to this tendency as well as the need to situate thinking and practice within a broader framework of understanding encompassing other traditions.

Unless educators can become clear about the metaphors that structure their thinking on the discipline, real conversation is impossible, for persons tend to redefine all conversation through their own position. (Seymour and Miller 1982, 31).

One of the great contributions of this book lies in the detailed exposition of each of the five approaches together with their strengths and limitations. These include religious instruction, faith community, spiritual development, liberation, and interpretation. All have different goals, views of the teacher, views of the learner, content, preferred settings for learning, curriculum, contributions, and problems. (Seymour and Miller 1982, 32-33).

The greater contribution of the book however is in its task of mapping out the broader contours of Christian education, expanding the scope and horizon of the discipline, giving voice to previously unfamiliar approaches, and seeking greater conversation and integration between the different approaches. Its greater contribution also lies in its ability to raise critical questions about current mindsets and practices of Christian education in churches. In what way does upholding a pre-commitment to just one approach stifle education development and imagination in the church? In what way does privileging one approach of Christian education over others impede the accomplishment of the church’s educational tasks of “proclamation,” “community,” “service,” “advocacy,” and “worship”? (Pazmiño 2008, 46-53). Is the ‘sage-on-the-stage’ approach prevalent in traditional Sunday schools and adult bible classes adequate for preparing God’s people for twenty-first century global missional responses expressed through evangelism, teaching, compassion work, social justice, and creation care? (Walls and Ross 2008).

In the same spirit of helping Christian educators to avoid falling into the trap of assuming a “one-size-fits-all” approach in Christian education, Issler and Habermas explore different processes by which people learn (Issler and Habermas 2002). Drawing from well-established research in educational psychology, they point out that learning is multi-faceted and involves cognitive, behavioral, affective, and dispositional components (Issler and Habermas 2002, 29-46). Learning across the facets necessarily involves a spectrum of processes – including learning by association, learning by example, and learning by processing information (and Issler and Habermas 2002, 49-96).

Likewise, Bruce helps Christian educators to transcend a narrow understanding of intelligence by introducing the seven intelligences proposed by Howard Gardner to the teaching ministries of the church (Bruce 2000). Gardner’s seven intelligences include verbal/linguistic, logical/mathematical, visual/spatial, body/kinesthetic, musical/rhythmic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligences (Gardner 1993). Here Bruce seeks to raise consciousness of a multiplicity of intelligences which frequently overlap with each other. In her words, “this overlap increases and enhances learning as it captures the best way of ‘knowing’” (Bruce 2000, 14).

The common thread that connects the insights presented by the authors above is that none assume one pedagogical “magic-pill” approach or modality with which to build faith, develop Christian maturity, and advance the Kingdom of God. All value holism and integration in approaching Christian education. All call for shifts away from educational reductionism and uncritical hegemonic tendencies in pedagogical practice at a time when change is touching every facet of society. All call for fuller orbed learning experiences in the church by which God’s people can be exposed to global missional concerns, established in the foundations of faith, and tutored in the ways of God.

Part 2: Forging the way forward: Considerations, concerns, and cautions

The invitation to introduce learning experiences which are multi-textured and multimodal presents a fresh direction in education for both church ministries as well as theological institutions. This call to action is in fact well-grounded in the research into differences in learning styles and modalities which has now birthed many voices advocating for educational variety and rich learning experiences (James and Galbraith 1985; Gardner 1993; Fleming 1995; Kolb 2013). Simply stated, “different people learn in different ways” and “teachers who rely exclusively on any one teaching approach often fail to get through to significant numbers of students.” (Meyers and Jones 1993, xi) In the current age of global connectivity, new media technologies, and educational reform, these truisms have acquired greater currency and hold out great appeal to both learners and educators.

The move towards offering fresh and meaningful educational blends in churches and theological institutions however is not unproblematic and without issue. Below therefore, I surface four considerations, concerns, and cautions for discussion and critical reflection.

Consideration 1: Embrace the push for an integrated development of a broad scope of learning outcomes.

Thomas Fuller (Fuller 2008) puts forth one of the more comprehensive lists of critical competencies, skills, capacities, attitudes, understandings, knowledge, dispositions, and behaviors to be developed for ministry. He divides his list into five broad categories: i) Leadership, ii) Pastoral Care, iii) Personal and Spiritual Issues, iv) Proclamation, v) Relational Skills. The following seventy-two items are included in his list:

- Leadership: Administrative practices, budgeting for ministry, business meeting moderation, communication skills (oral and written), developing leaders/mentoring, interpreting the ministry context, leading change, leading a Christian education ministry, leading the church in missions, leading stewardship emphases, managing conflict, organizational skills, planning and goal-setting, recruiting, training, and motivating volunteers, supervision of personnel, understanding of denominational polity and resources, understanding of financial reports and procedure, vision-casting, working with committee and other leadership group.

- Pastoral Care: Care for the poor, counseling, crisis care, encouragement, equipping others for caregiving, hospital visitation, marriage ministry, ministry to the bereaved, pastoral visitation/soul care.

- Personal & Spiritual Issues: Appearance, attitude, biblical authority, calling and giftedness, dealing with stress, love for God and for others, discipline, growth in faith, high ethical standard, initiative and work ethic, integration of theory and ministry practice, money management, practices spiritual disciplines, responsible and trustworthy, self-awareness, self-care, self-control, servant spirit, sexuality, teachable spirit, theological grounding for life and ministry, time management.

- Proclamation: Administering the Lord’s Supper/Holy Communion, equipping others through teaching, justice advocacy, organizing and leading others in outreach, performing Christian baptism, personal evangelism, preaching, training others for evangelism, worship planning and leadership.

- Relationship Skills: Dealing with difficult persons and situations, empathy, flexibility, listening, sense of humor, with peers in ministry (collegiality), with one’s family members, with persons in authority, with persons of different ethnic origin, with persons with disabilities, with persons of different ages, with persons of various socioeconomic status. (Fuller 2008, 187-210).

Fuller’s list reminds us that the scope of ministry development is very broad. Current thinking in seminary training and leadership development seeks to move beyond the development of head, hand, and heart in isolation. Instead, ministry preparation leans “toward the objective of bringing together the elements of knowing, being, and doing in ways that are meaningful in and extend beyond the classroom in sustainable practices of spiritual growth and ministry.” (Dirks 2006, 99).

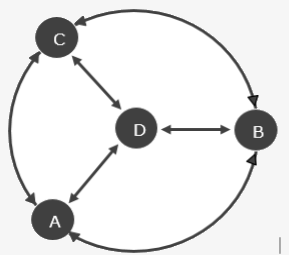

This push towards integrative learning is echoed by Perry Shaw in his recent book on transforming theological education. There, Shaw points to the fact that “learning is complex, and the physical, emotional, relational, cognitive, moral and spiritual aspects of the human person are closely intertwined.” (Shaw 2014, 69). In recognition of the complexity of learning involved in training for ministry, Shaw coined the phrase “The ABCD of learning” –– a phrase advocating the active development of multiple dimensions of learning (Shaw 2014, 67-76). These dimensions include the affective (A), behavioral (B), and cognitive (C) dimensions that work in concert to form the inner dispositions (D) of the learner. Figure 1 illustrates the interrelationship of the learning dimensions and how they interact with each other to develop transformed dispositions.

Figure 1: The interface of the learning dimensions (Shaw 2014, 76).

Shaw argues the importance of paying attention to all the dimensions of learning and noting how they relate to each other to transform the learner.

Only when these three dimensions are embraced in a holistic concert can fundamental transformation – dispositional learning – take place. Only through a multidimensional approach to education in seminary and church can our learners become increasingly disposed to think, feel, and act like Jesus – the ultimate goal of all Christian teaching (Eph 4:1-13) (Shaw 2014, 69).

Pressing his argument further, Shaw critiques the tendencies of theological institutions to focus largely on cognitive development thus resulting in the imbalanced development of graduates of seminary training. He thus warns against these imbalances while at the same time advocating for holism and integration in theological education:

An imbalance between the learning dimensions creates distortions in the disposition: a focus on the affective domain leads to ignorant pietism; a focus on the behavioural domain leads to empty technical excellence; a focus on the cognitive domain leads to the pride and irrelevance that are endemic among many theological graduates. Excellence in theological education will recognize the need for a holistic balance which will lead to the healthy dispositional formation of the emerging leaders entrusted to our care. (Shaw 2014, 76).

This push towards integrative learning attempts at reversing the fragmentation of learning that characterizes so much of theological education. For the movement to succeed however will require a reexamination of default classroom practices and a shift towards providing learning environments and experiences where the above mentioned dimensions purposefully interface with each other. The same applies to educational practices in church and on the mission field.

Here, the use of integrative multimodal learning experiences can make a valuable contribution toward this end. In the same spirit as David Kolb’s experiential learning model which seeks to connect concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb 1984, 40-43; Kolb and Kolb 2005, 194-195), so multimodal, multidisciplinary learning experiences and assessment strategies designed to foster integration of ministry outcomes will need to be more intentionally developed and extensively deployed for ministry preparation in the twenty-first century.

Consideration 2: Recognize the tension between efficient and efficacious educational practice.

One of the common realities faced by church ministries, training departments, and theological institutions is the scant availability of contact hours with participants coupled with the pressure to accomplish much within those limited hours. Conventionally, the traditional classroom lecture approach is assumed to be the best way to meet these expectations. Consequently, lecturing has served as the benchmark by which efficient education is attained and is routinely held out as the gold standard by which the success or failure of educational innovations is measured.

An objection to incorporating multimodal elements into participant learning experiences therefore is that the addition of communications modes erodes teaching efficiency. More is not necessarily better. It is often messier, distracting, and adds to teacher workload! This final point is supported by Nicholas Khoo’s observation about omnichannel communication[1].

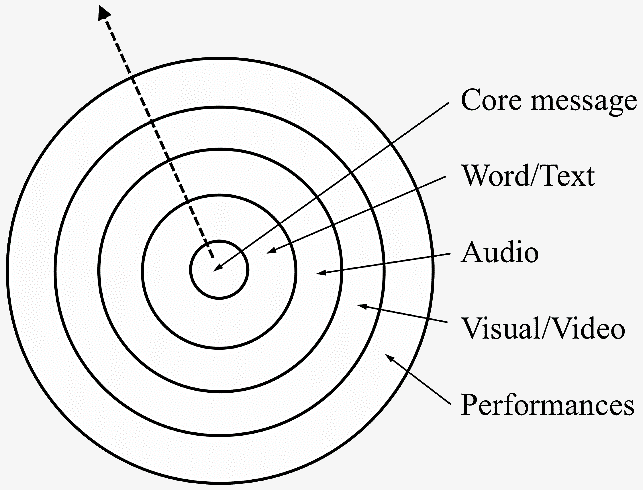

Size of layer correlates with the level of complexity of execution i.e. the outer layers are more difficult to execute than the inner layers.

Figure 2: Core message delivered in various forms and layers

Khoo’s point about omnichannel communication is that it reinforces a core message by deploying different communication forms across mainstream media, online platforms, performance stages, etc. However, he observes that the degree of complexity for planning and execution increases as one incorporates forms from the outer layers. In the context of the classroom, this push toward creating multimodal learning experiences imposes unreasonable demands on teachers’ time and expertise. It also raises red flags about counterproductive use of precious teaching hours.

Valid as they may seem, these concerns need to be balanced by indictments against traditional classroom methods for being “unengaging” and unimaginative. It is now widely recognized that providing copious quantities of content and striving for efficient delivery in classroom settings cannot be equated to effective learning. The saying “Just as learning can take place without teaching occurring, so teaching can take place without learning occurring” reminds us that there is no automatic correlation between the two.

The calling therefore is for teachers “to increase experiences of deep engagement, reduce the incidence of indifference and apathy that characterize lack of engagement, and attend to the many ways we can adapt our teaching methods to enhance engaged learning.” (Barkley 2009, 8). Instead of adopting binary thinking that pits efficiency against effectiveness and wide coverage of content against depth of learning, the way forward must seek integration of creative multimodal learning with rigorous and transformative learning. For these outcomes to materialize will require thought behind planned choices of modal mixes and effort to better craft well-designed learning experiences.

Consideration 3: Learn from other disciplines and be willing to experiment.

At the onset of the journey, it will need to be stated that any attempt to develop engaging multimodal, multidisciplinary educational experiences that effectively and efficiently catalyze deep and meaningful learning will be met by many challenges. The task is one that invites radical transformation of educational practices which runs against the grain of institutional culture. It is also one which stretches beyond the imagination, expertise, and capacity of any one ministry worker in church or any faculty member in seminary. It is for this reason that gleaning from industries and disciplines which already model creative multimodal, multidisciplinary learning, communications, and design thinking will be a useful exercise.

The cross-pollination of pedagogical, communications, and design ideas is already evidenced across a range of different arenas of society. Community theatre genres like forum theatre and playback theatre are presently used by professional bodies, the civil service, educational institutions, non-governmental organizations, and community groups to draw attention to issues that matter and to surface different voices that need to be heard. Theatre games and drum circles are used extensively to help working teams to listen to each other and experience the range of consequences arising from participant responses.

The gamification of learning, a recent adaptation of the online massively multiplayer role playing game (MMORPG), is now used in physical settings to help multidisciplinary response teams to learn content, work collaboratively, exercise good judgment, and find solutions to complex real world problems (Sheldon 2011; Kapp 2012; Kapp, Blair, and Mesch 2014). Story slams are used in many educational and social settings to tell personal stories of significance that provoke thought and advocate for change. PhotoVoice has proven effective for researching ground level social realities and injustices amongst the voiceless in society (Mitchell 2011; Delgado 2015; Moxley, Bishop, and Miller-Cribbs 2015).

The above serve as examples of how multimodal learning has already diffused across different professional, social, and educational arenas. Some will be highly appropriate and adaptable for use in churches, seminaries, and mission fields. Introduction to these educational ministries however will require a spirit of innovation and experimentation. Little steps forward such as collaborating with educational and communications specialists to organize a series of incubator events will allow for the piloting, evaluating, and documenting of multimodal learning experiences and their impact on learners.

Consideration 4: Avoid violating the covenant of communication.

A significant part of the training and educational ministries in churches, missions organizations, and theological institutions includes helping God’s people grow in their knowledge and understanding of scriptures. This work of fostering bible literacy is critical to the shaping of Christian mission and identity and hence central to the work of evangelism, apologetics, and Christian discipleship. Current efforts in reaching out to oral-preference learners and at introducing creativity in children’s/youth/campus ministries have ushered an explosion of creative approaches to promote bible engagement. Some of these artistic, imaginative, and sometimes entertaining approaches and activities include:

- Creative story telling (Hartman 2011, Koehler 2010; Terry 2010; Dillon 2012; Walsh 2014)

- Bible speech choirs and reader’s theatre (Brassard 1987; Davidson 1992; Biedinger 2011)

- Participatory scripture dramatization (Page 2005; Rowe 2010)

- Group storytelling/retelling (Novelli 2008; Novelli 2010)

- Godly play (Berryman 1991; Privett 2003; Berryman 2009)

- Bible graphic novels

- Bible board games

- Sand art bible storytelling

- Interpretive art/dance/drama/photography/photomontage of bible events

- Video stories and cartoon animations of the bible stories, and

- Multimedia mobile bible apps

Responsible multimodal Bible engagement ensures that both a high view of scripture and the high goals of Christian education are upheld. At its most basic level, a high view of scripture demands faithful interpretation, understanding, and representation of God’s word which in turn invites God’s people to submit their lives in obedience to that word. This in fact captures the effort and commitment of current evangelical leaders in the church and within the theological academy. The high goals of Christian education on the other hand present the whole counsel of God to his people and invite them to hide that word in their hearts. The pervasive presence of this counsel, meditated upon regularly and acted upon, catalyzes reverence and love for God, offers wisdom for living, enlarges concern for the world, and transforms the condition of the human heart. This in fact captures the blessing received when God’s word is rooted in Christian faith communities.

It is when there is deviation from basic principles of biblical hermeneutics, caricaturization of Scripture, and celebration of bastardized truncations of the whole counsel of God that concern is raised about the use of creative multimodal approaches. In every generation, these lapses have always been present. Professions of how pulpits, programs and practices are deeply rooted in God’s word have perennially been coupled with profound lack of awareness of how social location, theological identity, life experiences, cultural stories, and other pre-understandings color the understanding and use of scripture (Croy 2011, 1-12; Wilkens and Sanford 2009). Together with this often unconscious coloring, poor reading habits which ignore historical/literary contexts and selective omission of portions of the Canon also muffle and sometimes gag the voice of God in the theatre of improvisation, creativity and eloquence.

With the growth and development of multimodal learning experiences that communicate persuasively and reinforce learning effectively, the issues spelled out above will not wane unless churches, mission organizations, and the theological institutions commit themselves to “handle the word of truth accurately” (2 Tim 2:15). In the words of George Knight, “To handle this word correctly is to handle it in accord with its intention and to communicate properly its meaning.” (Knight 1992, 412). It is for this reason that whether it involves the study of written text, oral storytelling, or some other form of multimodal expression, the educational ministries of the church and on the mission field should hold their efforts accountable to a “covenant of communication.” Duvall and Hays explain the concept and its significance below:

Even though the author and reader cannot have a face-to-face conversation, they meet in the text where they are able to communicate because they subscribe to a common set of rules–the rules of the particular genre. In this way, literary genre acts as a kind of covenant of communication, a fixed agreement between author and reader about how to communicate. In order for us to “keep the covenant,” we must let the author’s choice of genre determine the rules we use to understand his words. To disregard literary genre in the Bible is to violate our covenant with the biblical author and with the Holy Spirit who inspired his message. (Duvall and Hays 2012, 151)

Here the unique contributions of theological institutions toward understanding biblical hermeneutics and exegesis of scripture should be noted and tapped on. In an age of networking and partnerships, more church collaborations, mission field and the theological academy should be forged for developing innovative forms of multimodal engagement with God’s word. This will allow theological institutions a share in the custodian role of safeguarding from highly midrashic multimodal presentations of God’s word while at the same time updating and exposing them to needed educational creativity and innovation.

Part 3: Examples of multimodal learning experiences

adapted for seminary classrooms, church, and the mission field

Multimodal communication and education draw their resources from multiple semiotic systems. What if professors, trainers, and Christian educators conceived of education as rich experiences that combined a range of these semiotic resources? What would learning experiences and assignments look like if instructional designers envisioned education in the twenty-first century as meaningful and memorable experiences that draw their vibrancy from multimodal communications elements? The possibilities are endless, but to begin the journey, I offer three examples that reflect a variety of learning events and activities. These three serve to illustrate multimodal learning to complement traditional teaching methods and can be readily adapted for seminary classrooms, church, and the mission field.

Example 1. Strangers in our midst: A simulation game about relating to outsiders in church.

The “Stranger in our midst” simulation game is a multimodal learning experience that opens conversations about a widespread phenomenon all around the world. This is the experience of strangers avoided, looked down on, or becoming invisible within the church. The activity involves participants taking out a piece of paper from an envelope and passed around. Each piece of paper has a role written on it. The roles include “preaching pastor,” “choir member,” “youth leader,” “prayer warrior,” “church elder,” “usher,” and “missionary.” Participants are instructed not to reveal their roles to each other at the start of the game. They then have three to five minutes to form same role groups. Participants can only communicate with each other using sounds, music, and gestures. They may not speak or write to identify their roles. Hands are raised when their group has been formed.

Amongst the other roles however, there will be one or two stranger role such as “migrant,” “foreigner,” “prostitute,” “handicapped,” “homosexual,” etc. slipped into the envelope. The result is that amidst the busyness of navigating their way to their own kind, there will be one or two people lost and unable to relate to the members already in their closed groups. The experience of the stranger and how Christians relate to strangers in church becomes the talking point during the debrief session which follows. The following questions may be used in the debrief:

- If you were an outsider, how would you describe what you just observed during the activity?

- What words would you use to describe the different feelings that were generated in this activity?

- Describe your own feelings. Why did you feel that way?

- Who are the people who are often neglected and unwelcomed in our churches? Why is that so?

- Are there instances when you intentionally should not welcome the neglected and unwelcomed to our churches? Share reasons why.

- If a few bible authors were in our midst, what would they have to say about strangers in our midst

- As a leader, what concrete steps can you take to ensure that your church is more friendly toward the neglected and unwelcome?

By way of follow-up, participants are asked to identify those who are avoided, looked down on, or invisible in their churches. Permission will be sought from church leaders to conduct interviews with them to find out why they come to church, what challenges they face when they come to church, and suggestions for a better experience that the church can offer. Findings are then brought back to the church leadership for review, discussion, and action. Participants then write a reflection paper based on what they learned from the classroom activity, discussions, interviews, and responses from church.

Example 2. Challenge activities: An alternative approach to traditional assessments.

Challenge activities are a list of mini projects that allow students to explore their interests and use their talents in relation to ideas and issues raised in their courses. Students are presented with one star, two star, and three star activities which help them to develop understanding, deepen convictions, and explore solutions encountered in their studies. Apart from the list of activities provided by the course instructor, students are also invited to propose their own one, two, and three star activities that allow them to customize their learning. The degree of difficulty increases with the number of stars an activity is assigned. Students must complete any combination to make a total of five stars. Kim Eun Hee, an MA in Intercultural Studies student, created the following challenge activities list for a “Ministry to Migrants” course at the Singapore Bible College. The list of twenty activities reflects a high level of multimodal learning as well as the integration of different domains of learning. One of the three star assignments she attempted–writing a children’s story about the migrant experience–is currently with a publisher and has the potential to be adapted for a play.

| Ministry to Migrant Challenge Activities | |

| Annotated Bibliography * |

Expand the course bibliography with new sources (books, articles, websites, organizations, etc). Include at least five new sources for the Ministry to Migrant class and annotate the additional references with a short summary of at least 100 words. |

| Movie List * |

Contribute a list of at least ten to fifteen movie titles (and documentaries) that feature migrants and/or their experiences and struggles. Write a brief synopsis for each movie in less than 100 words. |

| Photography

* |

Take an adventure to capture the variety of migrant experiences in Singapore. |

| List of NGO Directory * |

Search for at least 7 NGOs who work with migrants (local or international). Make a list of NGO directory that contains their website, address, scope of work and how to get involved. |

| Biblical Journey

* |

Focus on one character of the Bible who was a migrant and trace his or her journey. Write an analysis of 500 words about their migrant experience, exploring the struggles they faced and the different contributions or impacts they made to the host culture. |

| Movie Review

* |

Watch a movie that deals with migrants and write a movie review and personal reflection in 500 words. |

| Discussion Group

** |

Host a discussion group outside class (in church) that would meet at least 2 times to raise awareness of migrant issues and to share experiences to draw how to engage in ministry to migrants. |

| Survey & Report

** |

Create a survey to find out the attitudes, thoughts and perceptions that people in your church or your social circle have about migrants. Do a 500 word report on your findings. |

| Journal

** |

Write 10 journal entries reflecting on personal thoughts and opinions in response to what is taught in class. In each journal, choose an issue or theme (e.g. liminality, assimilation vs. diversity) that you would like to explore and write your personal views on them. |

| Book Summary

** |

Read a book (or journal article) about migrants and write a book summary and review of at least 1000 words. |

| Social Media Awareness ** |

Adopt a migrant group and create a social media account (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, blogs) that is updated regularly with content to help raise awareness to their situation and to encourage discussion and involvement. |

| Volunteer for a day ** |

Approach a NGO/church involved with migrant work in Singapore and volunteer for a day. Write a reflection paper about your experience in 1000 words or less. |

| Learning Journey and Reflection

*** |

Join a learning journey that allows you to explore firsthand the life of a migrant worker by viewing their workplace and dorm lives. Write a reflection that details what you saw and how you felt. |

| “Tell me your story”

*** |

Set aside a day to visit a space where many migrants gather, approach at least two to five and offer to hear their stories and migrant experiences. Your primary task is to listen to them and be present. (Try not to speak) Capture their stories (at least half a page per person) and also record your experience. |

| Writing a Children’s book

*** |

Be creative and write a children’s book that deals with migrants and their experiences. Focus on how to engage the children to be more sensitive and aware of the migrant presence in Singapore by emphasizing kindness towards them. |

| Ethnography Project

*** |

Befriend a migrant worker and spend a week shadowing him or her. Write a report of your observation and experience (1500 to 2000 words). Give a presentation to the class or in church. |

| Short Film on Migrants’ Lives

*** |

Create a short film about migrants and post it on YouTube. Capture a vivid and accurate reflection about their lives and struggles and experiences in Singapore. The film should not be longer than 15 minutes and creative. |

| Pray for Migrants

*** |

Create a prayer group and commit to pray daily for a chosen migrant group for two weeks. Keep a pray journal documenting the prayer meeting and prayer points. |

| Dinner with the Other

*** |

Befriend a few migrant workers and invite them over for a meal in your house and have a time of good fellowship. Document photos and write about your experience in 1000 words. |

| Life of the Other *** |

Immerse yourself in the struggles of a migrant worker. Spend a week limiting yourself to $3 a day for all your daily expenditure. This includes transport, food and leisure activities. Chronicle your daily experience: make a thorough record of how you spent each day and how you felt. Write a final reflection about your experience in 1500 words. |

Example 3. Group Bible study using text-mapping and drama games

This group Bible study activity involves the use of text mapping, map work, mind maps, and several drama games techniques including freeze frames, thought tracking, flashbacks and flash forwards. In their groups, students complete a series of learning tasks that help them to understand the bible text better. Text mapping is an activity that involves the use of a scroll, pens, highlighter markers, and any other resources needed to conduct a group learning activity. Relevant passages from the Bible are obtained from an online Bible website, printed in A3 size sheets, and then taped into a scroll. Working with their scrolls, maps, and charts, groups of students embark on a discovery journey of exploring the text, surfacing insights, and making applications.[2]

Freeze frame, thought tracking, flashbacks, and flash forwards are simple drama games used to explore the content in plays/texts more deeply. In a freeze frame, participants are asked to imagine they were acting out a particular scene and then asked to freeze. What results is a human still photo. Groups must explain their scene choices in order to establish the significance of their selections. Thought tracking is a technique used in conjunction with freeze frames. In thought tracking, selected participants are “unfrozen” to share scene roles, perspectives, and insights. Flashbacks and flash forwards allow groups to explore what went on before and after a particular freeze frame. Creating a series of freeze frames will allow students to explore the connections between different sections of the narrative.[3]

Below are the instructions for a classroom text mapping exercise based on Acts 13-14.

You have just received a telephone call from your senior pastor requesting you to take over the guest preacher’s role of preaching this Sunday. The passage that she was assigned is Acts 13-14 – Paul and Barnabas’ first missionary journey. The sermon is part of a sermon series on Acts in your church. In order to prepare for your sermon, please familiarize yourself with the text by participating in the following collaborative learning exercise:

- Take 5-10 minutes to read the text silently by yourself.

- Form groups of fours. In your groups, identify the key places which the missionaries visited on their journey. Indicate the chronological order in which the cities were visited on the map provided.

- Identify the characters encountered at each place, how they are characterized in the story, the challenges faced by Paul and Barnabas at each place, Paul and Barnabas’ responses to the challenges in each situation, and the outcome of their missionary efforts at each location.

- What similarities or common threads can we discover as we examine and compare the different scenes found in this missionary journey?

- Use the different colors to highlight themes and patterns in your findings and collate them in the chart provided.

- What important points from the text would you incorporate in your sermon on Paul’s first missionary journey?

- What applications can you make in your sermon on Paul’s first missionary journey?

- Drawing from your findings, create an outline or a mindmap which can be used to communicate the key ideas and applications from Acts 13-14 to your audience. You may use flipcharts, PowerPoint, or Prezi to present your key findings.

- In addition, prepare freeze frames of three key scenes in Acts 13-14. Explain the rationale behind the choice of scenes. All participants involved in each of the three scenes must be ready to respond to thought tracking by explaining what is happening at this point and your character’s contribution in the scene. Participants should also be ready to respond to requests to stage flashbacks or flash forwards.

Conclusions

As the future takes a turn towards multimodal communications and learning, church ministries, mission organizations, and theological institutions will need to review the form and nature of their educational offerings and communications strategies. The impetus to develop a multimodal mindset is captured in the metaphor of the growing gap between the single singer-guitarist who continues to sing to audiences that have grown up listening to rock groups, orchestras, Latin bands, jazz ensembles, and drumming groups. For the singer-guitarist, the scope of music is limited to the voice and his ability on the guitar. For the “experience generation” audience, the scope of music is limited only by the imagination of the artistes who have at their disposal a very large range of musical possibilities.

Like the singer-guitarist, educators need to go beyond preferences and personal limitations and enlarge their mental conceptions of what is possible on the educational stage. Pushing the metaphor further, they will need to expand their musicianship and learn to play as a band. Members of successful bands know that no single musician carries the full burden of performing a song. Instead all are required to listen to each other and to make space for others to introduce unique complementary elements which enrich the total experience. Strong advocates of learning-centered approaches to education will press a little more out of this metaphor to argue that educators should conceive of themselves more as music directors than members of the band. Like music directors, their roles are in mentoring and orchestrating learning experiences which allow students to take the role of the performers. In that way, their charges will be better prepared for service and ministry in a complex and uncertain multi-modal world.

Notes

[1] Presentation by Nicholas Aaron Khoo at a planning meeting on 20 June 2014.

[2] More information about text mapping can be found at http://www.textmapping.org/

[3] Other drama strategies which can be adapted for use can be found at the Drama Resources website. http://www.dramaresource.com/strategies

« 2016 NAR Conference Plenary Sessions Oralities & Literacies – Chapter 3 &#...»